Economy in Bed and Table-Linen

A traveller, domiciling at an American hotel, exclaimed one morning to the waiter,

“What are you about, you rascal? You have raised me twice from my sleep by telling me breakfast is ready, and now you are attempting to strip off the bedclothes.”

“What do you mean?” asked Pompey; “if you are goin’ to get up, I must hab the sheet anyhow, ‘cause we waiting for de table-clof”.

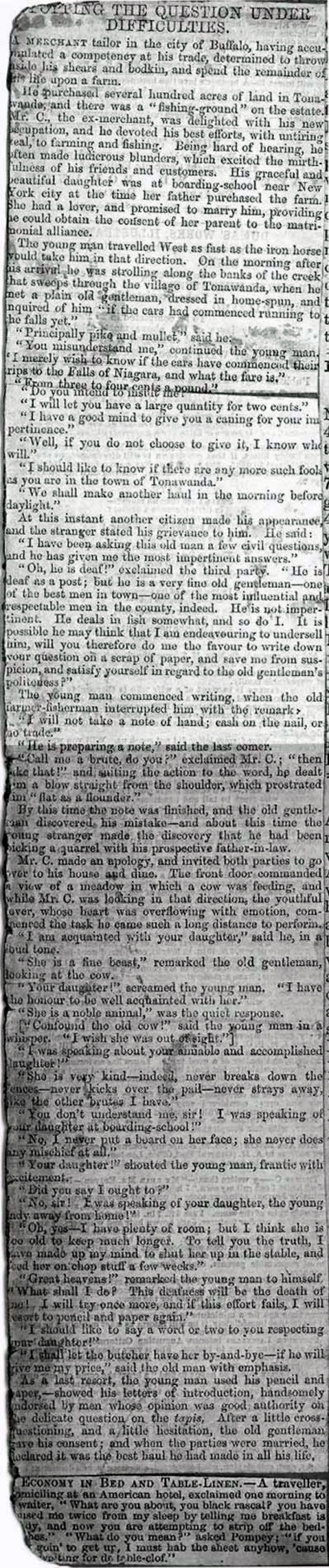

Popping the Question Under Difficulties

A MERCHANT tailor in the city of Buffalo, having accumulated a competency at his trade, determined to throw aside his shears and bodkin, and spend the remainder of his life upon a farm.

He purchased several hundred acres of land in Tonawanda, and there was a ‘fishing-ground’ on the estate. Mr. C., the ex-merchant, was delighted with his new occupation, and he devoted his best efforts, with untiring zeal, to farming and fishing. Being hard of hearing, he often made ludicrous blunders, which excited the mirthfulness of his friends and customers. His graceful and beautiful daughter was at boarding-school near New York city at the time her father purchased the farm. She had a lover, and promised to marry him, providing he could obtain the consent of her parent to the matrimonial alliance.

The young man travelled West as fast as the iron horse would take him in that direction. On the morning after his arrival he was strolling along the banks of the creek that sweeps through the village of Tonawanda, when he met a plain old gentleman, dressed in home-spun, and inquired of him “if the cars had commenced running to the falls yet.”

“Principally pike and mullet” said he.

“You misunderstand me,” continued the young man. “I merely wish to know if the cars have commenced their trips to the Falls of Niagara, and what the fare is.”

“From three to four cents a pound.”

“Do you intend to insult me!”

“I will let you have a large quantity for two cents.”

“I have a good mind to give you a caning for your impertinence.”

“Well, if you do not choose to give it, I know who will.”

“I should like to know if there are any more such fools as you are in the town of Tonawanda.”

“We shall make another haul in the morning before daylight.”

At this instant another citizen made his appearance, and the stranger stated his grievance to him. He said:

“I have been asking this old man a few civil questions, and he has given me the most impertinent answers.”

“Oh, he is deaf!” exclaimed the third party. “He is deaf as a post; but he is a very fine old gentleman – one of the best men in town – one of the most influential and respectable men in the county, indeed. He is not impertinent. He deals in fish somewhat, and so do I. It is possible he may think that I am endeavouring to undersell him, will you therefore do me the favour to write down your question on a scrap of paper, and save me from suspicion, and satisfy yourself in regard to the old gentleman’s politeness?”

The young man commence writing, when the old farmer-fisherman interrupted him with the remark –

“I will not take a note of hand; cash on the nail, or no trade.”

“He is preparing a note,” said the last comer.

“Call me a brute, do you?” exclaimed Mr. C.; “then take that!” and suiting the action to the word, he dealt him a blow straight from the shoulder, which prostrated him “flat as a flounder.”

By this time the note was finished, and the old gentleman discovered his mistake – and about this time the young stranger made the discovery that he had been picking a quarrel with his prospective father-in-law.

Mr. C. made an apology, and invited both parties to go over to his house and dine. The front door commanded a view of a meadow in which a cow was feeding, and while Mr. C. was looking in that direction, the youthful over, whose heart was overflowing with emotion, commenced the task he came such a long distance to perform.

“I am acquainted with your daughter,” said he, in a loud tone.

“She is a fine beast,” remarked the old gentleman, looking at the cow.

“your daughter!” screamed the young man. “I have the honour to be well acquainted with her.”

“She is a noble animal,” was the quiet response.

“Confound the old cow!” said the young man in a whisper. “I wish she was out of sight.”

“I was speaking about your amiable and accomplished daughter.”

“She is very king – indeed, never breaks down the fences – never kicks over the pail – never strays away, like the other brutes I have.”

You don’t understand me, sir! I was speaking of your daughter at boarding-school.”

“No, I never put a board on her face; she never does any mischief at all.”

“Your daughter!” shouted the young man, frantic with excitement.

“Did you say I ought to?”

“No, sir! I was speaking of your daughter, the young lady away from home!”

“Oh, yes – I have plenty of room; but I think she is too old to keep much longer. To tell you the truth, I have made up my mind to shut her up in the stable, and fed her on chop stuff a few weeks.”

“Great heavens!” remarked the young man to himself, “What shall I do? This deafness will be the death of me! I will try once more, and if this effort tails, I will resort to pencil and paper again.”

I should like to say a word or two to you respecting your daughter!”

“I shall let the butcher have her by-and bye – if he will give me my price,” said the old man with emphasis.

As a last resort the young man used his pencil and paper, - showed his letters of introduction, handsomely endorsed by men whose opinion was good authority on the delicate question of the tapis*. After a little cross-questioning, and a little hesitation, the old gentleman gave his consent; and when the parties were married, he declared it was the best haul he had made in all his life.

*On the tapis can mean under consideration