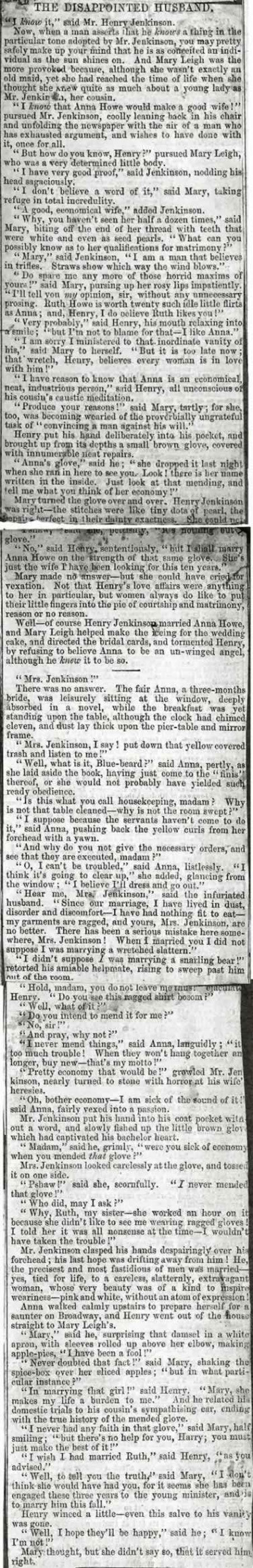

THE DISAPPOINTED HUSBAND.

“I know it,” said Mr. Henry Jenkinson.

Now, when a man asserts that he knows a thing in the particular tone adopted by Mr. Jenkinson, you may pretty safely make up you mind that he is as conceited an individual as the sun shines on. And Mary Leigh was the more provoked because, although she wasn’t exactly an old maid, yet she had reached the time of life when she thought she knew quite as much about a young lady as Mr. Jenkinson, her cousin.

“I know that Anna Howe would make a good wife!” pursued Mr Jenkinson, coolly leaning back in his chair and unfolding the newspaper with the air of a man who has exhausted argument, and wishes to have done with it, once for all.

“But how do you know, Henry?” pursued Mary Leigh, who was a very determined little body.

“I have very good proof,” said Jenkinson, nodding his head sagaciously.

“I don’t believe a word of it,” said Mary, taking refuge in total incredulity.

“A good, economical wife,” added Jenkinson.

“Why, you haven’t seen her half a dozen times,” said Mary, biting off the end of her thread with teeth that were white and even as seed pearls. “What can you possibly know as to her qualifications for matrimony?”

“Mary,” said Jenkinson, “I am a man that believes in trifles. Straws show which way the wind blows.”

“Do spare me any more of those horrid maxims of yours.” Said Mary, pursing up her rosy lips impatiently. “I’ll tell you my opinion, sir, without any unnecessary prosing. Ruth Howe is worth twenty such idle little flirts as Anna; and, Henry, I do believe Ruth likes you!”

“Very probably,” said Henry, his mouth relaxing into a smile; “but I’m not to blame for that – I like Anna.”

“I am sorry I ministered to that inordinate vanity of his,” said Mary to herself. “But it is too late now; that wretch, Henry, believes every woman is in love with him!”

“I have reason to know that Anna is an economical, neat, industrious person,” said Henry, all unconscious of his cousin’s caustic meditation.

“Produce your reasons!” said Mary, tartly; for she, too, was becoming wearied of the proverbially ungrateful task of “convincing a man against his will.”

Henry put his hand deliberately into his pocket, and brought up from its depths a small brown glove, covered with innumerable neat repairs.

“Anna’s glove,” said he; “she dropped it last night when she ran in here to see you. Look! There is her name written in the inside. Just look at that mending, and tell me what you think of her economy!”

Mary turned the glove over and over. Henry Jenkinson was right – the stitches were like tiny dots of pearl, the repairs perfect in their dainty exactness. She could not....

“Pshaw,” said she, pettishly, “It’s nothing but a glove.”

“No,” said Henry sententiously, “but I shall marry Anna Howe on the strength of that same glove. She’s just the wife I have been looking for this ten years.”

Mary made no answer – but she could have cried for vexation. Not that Henry’s love affairs were anything to her in particular, but women always do like to put their little fingers into the pie of courtship and matrimony, reason or no reason. Well – of course Henry Jenkinson married Anna Howe, and Mary Leigh helped make the iceing for the wedding cake, and directed the bridal cards, and tormented Henry, by refusing to believe Anna to be an un-winged angel, although he knew it to be so

“Mrs. Jenkinson!”

There was no answer. The fair Anna, a three-months bride, was leisurely sitting at the window, deeply absorbed in a novel, while the breakfast was yet standing upon the table, although the clock had chimed eleven, and dust lay thick upon the pier-table and mirrot frame.

“Mrs. Jenkinson, I say! Put down that yellow covered trash and listen to me!”

"Well, what is it, Blue-beard?” said Anna, pertly, as she laid aside the book, having just come to the “finis” thereof, or she would not probably have yielded such ready obedience.

“Is this what you call housekeeping, madam? Why is not that table cleaned – why is not the room swept?”

“I suppose because the servants haven’t come to do it,” said Anna, pushing back the yellow curls from her forehead with a yawn.

“And why do you not give the necessary orders, and see that they are executed, madam?”

“O, I can’t be troubled,” said Anna, listlessly. “I think it’s going to clear up,” she added, glancing from the window; “I believe I’ll dress and go out.”

“Hear me, Mrs. Jenkinson,” said the infuriated husband. “Since our marriage, I have lived in dust, disorder and discomfort – I have had nothing fit to eat – my garments are ragged, and yours, Mrs. Jenkinson, are no better. There has been a serious mistake here somewhere, Mrs. Jenkinson! When I married you I did not suppose I was marrying a wretched slattern.”

“I didn’t suppose I was marrying a snarling bear!” retorted his amiable helpmate, rising to sweep past him out of the room.

“Hold, madam, you do not leave me thus;” ejaculated Henry. “Do you see this ragged shirt bosom?”

“Well, what of it?”

“Do you intend to mend it for me?”

“No, sir!”

“And pray, why not?”

“I never mend things,” said Anna, languidly; “it’s too much trouble! When they won’t hang together any longer, buy new – that’s my motto!”

“Pretty economy that would be!” growled Mr. Jenkinson, nearly turned to stone with horror at his wife’s heresies.

“Oh, brother economy – I am sick of the sound of it!” said Anna, fairly vexed into a passion.

Mr. Jenkinson put his hand into his coat pocket without a word, and slowly fished up the little brown glove which had captivated his bachelor heart.

“Madam,” said he, grimly, “were you sick of economy when you mended that glove?”

Mrs. Jenkinson looked carelessly at the glove, and todded it on one side.

“Pshaw!” said she, scornfully. “I never mended that glove!”

“Who did, may I ask?”

“Why, Ruth, my sister – she worked an hour on it because she didn’t like to see me wearing ragged gloves! I told her it was all nonsense at the time – I wouldn’t have taken the trouble!”

Mr. Jenkinson clasped his hands despairingly over his forehead; his last hope was drifting away from him! He, the precisest and most fastidious of men was married – yes, tied for life, to a careless, slatternly, extravagant woman, whose very beauty was of a kind to inspire weariness – link and white, without an atom of expression!

Anna walked calmly upstairs to prepare herself for a saunter on Broadway, and Henry went out of the house straight to Mary Leigh’s.

“Mary,” said he, surprising that damsel in a white apron, with sleeves rolled up above her elbow, making apple-pies, “I have been a fool!”

“Never doubted that fact!” said Mary, shaking the spice-box over her sliced apples; “but in what particular instance?”

“In marrying that girl!” said Henry. “Mary, she makes my life a burden to me.” And he related his domestic trials to his cousin’s sympathising ear, ending with the true history of the mended glove.

“I never had any faith in that glove,” said Mary, half smiling; “but there’s no help for you, Henry; you must just make the best of it!”

“I wish I had married Ruth,” said Henry, “as you advised.”

“Well, to tell you the truth,” said Mary, “I don’t think she would have had you, for it seems she has been engaged these three years to the young minister, and is to marry him this fall.”

Henry winced a little – even this salve to his vanity was gone.

“Well, I hope they’ll be happy,” said he; “I know I’m not!”

Mary thought, but she didn’t say so, that it served him right.